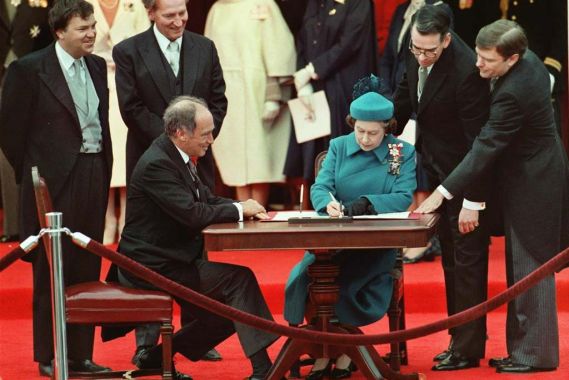

Under the Constitution, the sovereign remains officially Canada’s head of state, regardless of who holds the position at any given time. (Photo: The Canadian Press)

Ottawa — As solemn and historic as the death of Queen Elizabeth II may be, after 70 years of reign, little has changed Thursday when it comes to governance in Canada.

Under the constitution, the sovereign remains Canada’s official head of state, regardless of who holds the position at any given time, says Philippe Lagassé, associate professor of international affairs at Carleton University and an expert on the crown’s role in so-called “Westminster.” ” Parliamentary system.

Therefore, the Queen’s succession to her eldest son, Charles, will be automatic, without prejudice to governing bodies acting on her behalf, or laws, oaths, and other legal documents issued on her behalf.

“This transition does not require any action on the part of Canada,” said Professor Lagassé. The saying: “The Queen is dead, long live the King!” applies here as it does in Great Britain.”

In ‘common law’, Professor Lagassé recalls, the Queen and King are ‘the same legal entity’ because the Crown is a so-called ‘individual legal entity’.

“This means that the legal personality of the Queen (or the King) in her official capacity does not change when different individuals hold office. This further means that all legal documents and deeds in the Queen’s name or in which the Queen is mentioned are automatically valid and deemed to have been issued by the Queen. [nouveau] King.”

This is reminiscent of the Oath of Allegiance to the Crown, required in a variety of circumstances, including appointment as MP, member of the Canadian Armed Forces or Canadian citizen. “So there’s no need to ‘re-summon’ or ‘re-sign’ anything,” says Mr. Lagassé.

Parliament does not have to be dissolved

But that wasn’t always the case. In the past, the death of a monarch meant that parliaments sitting on his or her behalf in the United Kingdom and its colonies, including those that became Canada, were automatically dissolved and elections had to be held.

The so-called “dissolution by devolution of the crown” proceeded from the “premise that it was the sovereign who convoked a parliament in a personal capacity, and that therefore a parliament should die with the king or queen convened him”, says James Bowden, a recognized authority on these matters, in an April 2021 post on his academic blog Parliamentum.

This practice actually reflected “an older medieval status of the crown” when parliaments seldom met and were convened by the monarch only when necessary, Mr Bowden recalls. This has evidently become “impractical and disruptive” in more recent times, as parliaments have begun to meet regularly and the role of the monarch has become more ceremonial.

Dissolution by devolution of the crown was abolished in the United Kingdom in 1867, and the newly created Parliament of the Canadian Confederation followed suit at its first session that same year, Bowden said.

Today, the Parliament of Canada Act expressly states at the outset that “the conferral of the Crown shall not serve to suspend or dissolve Parliament, which may continue to function as if there had been no conferral”.

Likewise, the oath of citizenship was changed to swear allegiance to the Queen and “her heirs and successors”, specifically removing the need to re-swear the oath to a new monarch.

Quebec had to hurry

The provinces and territories have all enacted similar regulations. However, in its eagerness to remove references to the monarch from the National Assembly Act in 1982, Quebec also removed a provision that specifically stated that the legislature would not automatically dissolve upon the sovereign’s death.

Historians and constitutional experts have sounded the alarm, arguing that the omission could plunge Quebec into a general election once the queen dies – and potentially mean all laws passed after her death would be repealed. The Quebec government introduced legislation in March 2021 to rectify this omission, and the “Crown Transfer Act” was eventually passed in June 2021 – still just 15 months before the Queen’s death.

While the business of government in Canada continues undisturbed, Mr. Lagassé reminds that certain “formalities” must still be followed. For example, the Queen’s Privy Council for Canada, which includes all current and former ministers, must meet when a new monarch ascends the throne. The governor-general, the crown’s representative in Canada, must also issue a proclamation on the new monarch.

“However, it is important to note that this move only confirms what has already happened legally,” Mr Lagassé said.

There is also a special protocol about the official mourning period, which the governor-general’s office declined to discuss in advance.

Avid beer trailblazer. Friendly student. Tv geek. Coffee junkie. Total writer. Hipster-friendly internet practitioner. Pop culture fanatic.