What is this new novel about?

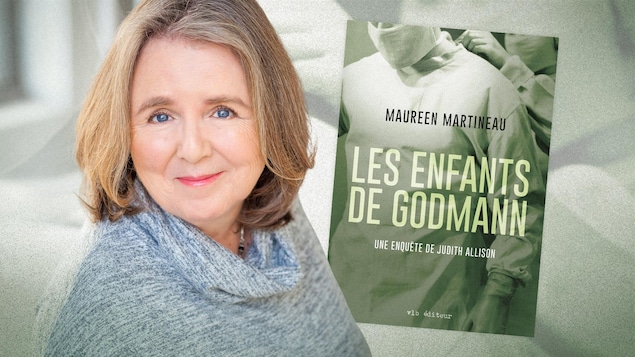

Godmann’s children, it’s an investigation led by Judith Allison, a young single police officer in her 30s. She lives in Wakefield and works for a police service I invented, the Outaouais Regional Police Service. She is asked about a crime that happened at Hull Hospital: One morning we find an octogenarian, Viktor Godman, dead. It’s suspicious because apparently we neutered him. Is this a medical error? A crime committed by hospital staff?

As we see him [M. Godmann] had visitors from Alberta the day before, […] Judith Allison will investigate in Alberta. Here we discover the full history of the psychiatric institutions of that time. to deeramong other things there was the Provincial training school where sexual sterilizations were performed on patients.

It also deals with the healthcare system at Hull Hospital. All of the action will take place in February and March 2020 ahead of the pandemic. But just as today, we are still concerned with issues such as forced overtime and overworked staff, which create criminal conditions due to poor supervision and perhaps professional distress.

How did the character of Judith Allison come to you?

When I decided to write this crime series 10 years ago, I wanted to create the character of a young detective. Me, I’m not young so I projected myself! [rires] It’s a beautiful young dark haired woman, 30 years old, who started [sa carrière] in The Ogre Game. I was inspired a bit by my daughter who is very rational, determined but emotional at the same time. He is someone who tackles it, but also makes mistakes. And I didn’t want Judith to be perfect: I wanted her new, daring. I wanted her to evolve through each of the surveys. She’s going to go through horrible stories, and I wanted to see the impact meeting people have [ces défis]. Also with this story Godmann’s childrenshe will be really concerned and she will be challenged in his private life.

Much of the action in this novel takes place in Wakefield. Why did you choose this region?

I’m from Outaouais. We’ve had a cottage in Cascades for a long time, not far from town farm point. The Gatineau River is our river. All our family, all my brothers are still here so we almost worship that river.

I’m very, very attached to it: it’s emotional! It’s something very sacred for me to install in one of the places I love most in the world, even though I don’t live there anymore. [puisque] I’m in Center-du-Québec now. There is already a police station, that of MRC des Collines, but I have set up a regional station where it will work fat bike » [vélos à pneus surdimensionnés] along the river. It’s wonderful, as a work life it’s a dream!

I thought it would be an interesting place for an investigator to settle, to reflect, and for the landscape to reflect everything she’s about to go through. For example, when she needs to think, she stands at the edge of the river. It’s February, it’s cold, but she has a dialogue with the river: the water helps her see clearly in the big decisions she has to make.

What is the importance of places and territories when writing a thriller?

It is important. In the beginning, when I started setting my thrillers in rural areas, in small villages in Centre-du-Québec, it was a choice. It’s very different. Crime marries the place. It’s not the same type of crime we’ll find on farms in Centre-du-Québec [qu’ailleurs]. It’s not the same plots, the same characters, or the same culture. For example, in a sugar bush it is so easy to hide a corpse. Guys you try to interrogate them but they are all cousins and they will all cover it up. Nobody will tell anything. There’s something about the place that drives the plot you write.

Health system issues figure prominently in this novel, particularly in the Hull sector. What did you want to highlight, especially in the pre-pandemic context?

When I came to give a presentation at the Chelsea Library The matchstick townwas attended by the former Mayor of Hull, Michel Légère. I had said that I would like to talk about the healthcare system in my next novel because I like medical crimes and we don’t write many about it among French-speaking authors. After that he came to me and quoted a paper he had written with two colleagues on the Barrette reform and its impact on the Pontiac. I read that and it was so enlightening: there were really interesting solutions that had been found throughout Pontiac back then, before the reform, including for hospitals and connections to community organizations. Everything was reversed with the Barrette reform. I told myself that not only do we have problems with our healthcare system, but when there are interesting solutions, it is often swept away. It made me seek even more inspiration from this health crisis.

There was that too Outaouais Emergency Department Black Book, which was written in 2018. It was written by about fifty nurses, nurses and orderlies. I relied heavily on this to describe the atmosphere in the hospital through this story by Godmann. It also becomes the scene of the crime, that hospital room that is not monitored because nobody has time for it. The crime writer in me saw this as an opportunity to say to myself: My god, a crime shouldn’t happen!

.

This text is based on an interview conducted by culture reporter Kevin Sweet. Comments may have been edited for clarity and conciseness.

Award-winning entrepreneur. Baconaholic. Food advocate. Wannabe beer maven. Twitter ninja.